“I’m a strong advocate of participative management. Motivation and commitment result from getting people involved-but I can’t always do it. Teamwork just isn’t practical in emergency situations.”

“There’s too much firefighting this organization for us to practice management by participation. I’m not going to be caught fiddling around getting consensus while my operation burns.”

“A team approach is effective for routine decisions. . . when there’s no pressure or time limit, but around here, ‘they’ want everything done yesterday. In a crunch, my boss expects action not discussion.’”

The merits of involvement and participation for optimizing organization effort are well documented and widely accepted. Over the past two decades, participative, team-oriented management has significantly improved the quality of organization life while enhancing productivity and creativity. Many organizations report substantial contributions to bottom-line results through consistent application of open leadership practices.

Nevertheless, managers often express the conviction that management by participation is limited to routine circumstances. While they pay lip service to its benefits, many managers silently view participation as too difficult, too time-consuming or too weak. If a problem or crisis arises, teamwork, if practiced at all, is necessarily suspended by managers who are convinced that power, authority, and control are essential to successful resolution.

Others suggest that participative management is situation-specific. It applies, they assert, to some situations with some subordinates but is inefficient and ineffective in situations containing an element of danger or crisis, or when the subordinate is capable of functioning independently. An important experiment involving an organization development firm and a major airline suggests critical flaws in the conventional wisdom view of what constitutes strong, effective leadership in crisis situations and demonstrates the utility of participative management in even the most threatening, danger-laden situations.

Official studies of airline industry accidents and near misses cite “human error” as the causative factor in 80 percent of the incidents investigated, an important NASA publication concludes, “One of the principle causes of incidents and accidents in civil jet transport operations is the lack of effective management of available resources by the flight deck crew.”1 NASA’s findings and related industry research help clarify the direct relationship between leadership processes and flight safety. In the airliner cockpit, traditional, authoritative leadership is often dangerous and sometimes fatal.

One major airline responded to the need for providing alternative leadership approaches and improving cockpit resource utilization by seeking the involvement of behavioral science experts in a joint safety-enhancing effort. Seven airline officers and seven organization development specialists formed a task force to identify and provide the skills required for exercising more effective leadership and teamwork in the cockpit. The airline staff contributed technical expertise and direct flying experience to the project, while members at the organization development firm offered valuable insight into underlying human dynamics and application of behavioral science theory and principles to sound leadership practice’

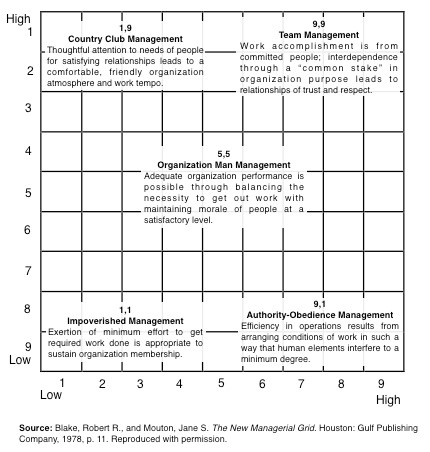

After 18 months of study and analysis, a systematic framework identifying various options for the exercise of cockpit leadership was completed. The basic Grid® structure, as represented in Figure I (9,1 1,9 1,1 5,5 and 9,9), was used as a point of departure; then special adaptations specific to the cockpit environment were made.2 A skills development seminar was designed to present these options to captains and crew members and to accomplish the objective of improved flight safety through 9,9-oriented leadership and teamwork.

More than 5,000 airline industry captains and crew members have since participated in the Cockpit Resource Management Seminar. During the seminar sessions, flight personnel experience the various leadership options firsthand through simulations and instrumented team learning designs. Strengths and limitations of these five styles are then evaluated for both routine and emergency flying circumstances. By an overwhelming majority, seminar participants conclude that 9,9 is the most effective style of cockpit leadership, especially under crisis conditions.

Lack of time is rarely a factor in averting disaster. In a matter of seconds, skilled professionals can communicate even complex data to one another. By providing other crew members an opportunity to contribute their input and perspective, the captain helps ensure a safe solution. When sound leadership is consistently applied across a range of situations, teamwork provides the key to generating superior alternatives and taking optimal actions.

There are at least five significant differences between the conventional view and a sound model of leadership at the point of crisis. Perhaps the most obvious difference involves the processes tor decision making. At issue is not “who” makes the decisions when an emergency arises, but “how” the decision is made. Both approaches recognize the ultimate responsibility and accountability of the leader, but hold opposing views as to the appropriate use of decision-making authority. Traditionally, crises are resolved through unilateral, authoritative decisions. Implementation depends primarily on the leader’s power and position. Alternatively, a 9,9-oriented leader withholds a final decision pending team member involvement and participation. Shared understanding and mutual agreement are the keys to cooperative, coordinated action.

Most organizations employ “early warning systems” for pointing up potential trouble spots and allowing timely action to avert disaster. Though few are as complex and sophisticated as those used in modern jet aircraft, almost all “detection” systems rely on people to “read” signals and initiate action. Inquiry involves constant, proactive monitoring of the organization’s danger signs to ensure consistency between intended and actual outcomes. In an effective team, members’ observations of the environment are freely offered and receive the leader’s serious attention. Measuring progress toward established objectives becomes a shared responsibility. Leaders operating from the conventional mode are more likely to interpret members’ observations as inappropriate questioning or unwarranted criticism. Team members may learn to withhold their warnings, even when danger is imminent.

I was the first officer on a flight into Chicago O’Hare. The Captain was flying, we were on approach and moving along about 250 knots. Approach control told us to slow down to 180 knots. I acknowledged and waited for the captain to slow down. When he failed to respond, I repeated, “Approach said to slow to 180.” His comment was, “You just look out the damn window.” Approach control called again, “Why haven’t you slowed down yet?…You almost hit another aircraft.”3

Under similar conditions, this cockpit team member might think twice about volunteering information or observations to the conventionally oriented Captain.

Advocacy is another critical element of teamwork effectiveness that is viewed differently from conventional and sound leadership perspectives. When a problem arises, the 9,9-oriented leader is open to solutions and recommendations proposed by others. Effective team members are responsible for openly and directly expressing their ideas, doubts, reservations or misgivings. Though the leader ultimately determines the course of action to be followed, intervening discussion of options increases the chances of adopting a sound strategy. In contrast, advocates of positions contrary to those held by conventional leaders may be perceived as disloyal or insubordinate. Conventional oriented leaders prefer acceptance and compliance to advocacy, and the quality of the eventual solution often suffers as a result.

A model of sound leadership recognizes that conflict is probably inevitable, particularly when members are encouraged to express their thoughts and opinions. Potential negative and destructive consequences of unresolved in emergency situations, because apparent conflict is surfaced, explored and resolved.

Conflict resolution is focused on what rather than who is right and provides a foundation for mutual trust and respect, deeper issue analysis, better problem definition, and improved solutions. The conventional approach to conflict is to squelch it before its “insidious” and “divisive” effects are felt. Disagreements or differences of opinion are viewed as problematic and unacceptable and are often “settled” by a win/lose appeal to power and authority. While it may be possible to submerge conflict in the short term, the longer-term frustration, resentment and latent hostility which result often emerge in counterproductive, anti-organization activities.

Finally, critique is an important element of sound leadership and team effectiveness, because it provides a framework whereby members can learn from experience. Through a process of preplanning, ongoing feedback, and postmortem evaluation, effective teams examine their successes as well as their failures. Future action in crises is strengthened through ongoing analysis of cause and effect and continuous performance improvements. Mistakes of the past are consciously avoided. Conventional wisdom applies critique primarily as a means of placing blame or fixing responsibility for errors. Only failure is seen as a potential learning experience-successes are savored, not studied.

In business, industry and government, effective action in crisis situations is a critically important measure of managerial performance. Proper planning and anticipation can prevent routine recurring problems from assuming crisis proportions, but unexpected developments characteristic of today’s complex organizational environment cannot always be predicted. When avoidance of these potentially disruptive situations is impossible, strong effective crisis leadership can make the difference between successful resolutions and disaster.

In every contemporary organization, managers at all levels make decisions under difficult and trying conditions. Poor decisions, particularly in emergencies, may be individually and organizationally costly. Sound leadership and effective teamwork results in better utilization of human resources and improved management of organization crises. Involvement and participation among team members results in higher quality solutions to which those involved are committed. Successful crisis resolution earns for the manager increased respect from superiors, colleagues, and subordinates.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the formulation of sound leadership and effective teamwork presented here.

First, 9,9-oriented leadership as defined in The New Managerial Grid4, has a wider range of practical utility for the management of crisis than previously thought. Its applicability to crises and emergency situations has been concretely demonstrated in one of the most demanding of all environments-the airliner cockpit. The skills of effective leadership and teamwork may be beneficial in other hazardous settings as well. Life-threatening crises experienced on the nuclear plant floor, in the provision of police and fire protection and in other high-risk environments and teamwork.

In the corporate setting, crises may be less dangerous or threatening in terms of risk to life and limb, but they are no less critical to those responsible for maintaining organization health and vitality. Organizations can avoid highly disruptive or potentially destructive situations through the consistent practice of management through participation. Inquiry, advocacy and open leadership are essential if American industry is to compete effectively with its Japanese counterparts. Japan perhaps owes as much of its success to ineffective American teamwork as to its own actions and initiatives. In this sense, Toyotas and Datsuns were made in Detroit as well as in Tokyo. Strong leadership and effective teamwork in the future may be the key to healing American businesses’ and industries’ current ails.

References

- Cooper, G. E., White, M. D., and Lauber, J. K. (Eds.) Resource management on the flight deck. Moffett Field, calif.: NASA’ 1980, 3. ,

- Blake, R. R., Mouton, J. S., and Command/ Leadership Resource Management Steering Committee, United Airlines, Cockpit Resource Management. Austin, Texas: Scientific Methods, Inc., 1982.

- Foushee, H.C. The role of communications socio-psychological and personality factors in the maintenance of crew coordination. Aviation, space and environmental medicine, in press.

- Blake, R.R. and Mouton, J.S. The new managerial Grid. Houron, Texas: Gulf Publishing Company, 1978.

Robert R. Blake, Ph.D. and Jane S. Mouton Ph.D.

Dr. Robert R. Blake and Dr. Jane S’ Mouton are, respectively, president and vice president of Scientific Methods, Inc., an organization widely respects for its behavioral science services to business and industry. Prior to forming their organization, they taught for a number of years at the University of Texas.

Dr. Blake is a member of numerous professional societies, is on the board of editors for a number of behavioral science journals, and is a trustee of the Institute of General Semantics. Dr. Mouton is a Diplomat in industrial psychology and is a member of numerous professional associations. Individually and in joint authorship, they have written several books and hundreds of articles and research papers papers. Their first work on the Grid concept, “The Managerial Grid” became one of the best-selling business books. IT has been revised and printed as “The New Managerial Grid®”. Drs. Blake and Mouton have coordinated the INCREASING PRODUCTIVITY AND EFFICIENCY program, two film series, MANGERIAL GRID®, AND SALES GRID®, as well as the film, Supervisory Grid®. All are available from BNA Communications, Inc.

Scientific Methods conducts Managerial Grid, Critique and Supervisory Grid seminars for strengthening the effectiveness of executives, managers, administrators and supervisors through experienced-based learning. For seminar information, contact Scientific Methods, Inc., Box 195, Austin, Texas 78767.