04

May, 21

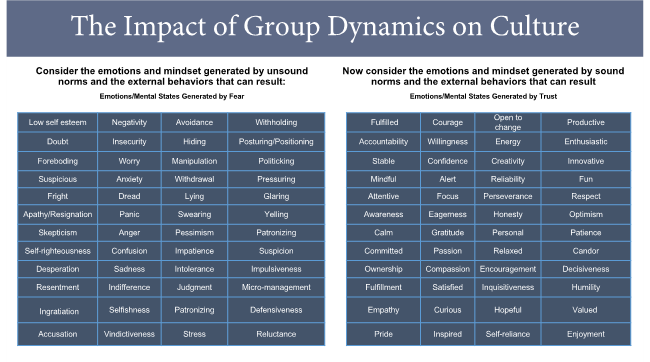

The key to changing norms is to shine a bright light on them. Allow those controlled by them to study them and explore alternatives that might better serve “What’s right” objectives. When the norm is shifted, altered attitudes and behavior shifts emerge. Norm-setting strategies are most acceptable when they are consistent with other organization-wide efforts to pursue corporate excellence.

There are benefits to gaining an understanding of group dynamics to motivate sustainable and resilient culture change:

A chaos of conflicting, reluctant, and confused responses develop every time a change is introduced. This chaos provides the leader with a critical opportunity to influence change, because within the confusion lie valuable energy and emotion. The formidable forces of conformity, cohesion and convergence can be used to create order out of chaos and shift opinions around new group norms—hopefully ones that are collectively and passionately pursued.

Norms and standards can easily manage behavior. However, through awareness, the process can reverse. People can manage norms and standards and, by doing so, harness the power to change. Companies that succeed in staying on the cutting edge of competition all have one thing in common: there are no sacred cows. They question everything and constantly challenge norms so that complacency never sets in.

If you think you are above the influence of culture, you are very wrong. Recent books by Malcomn Gladwell and Atul Gawande, both best-selling authors and staff writers for New Yorker Magazine, make dramatic points about how we perceive culture. In “Outliers,” Gladwell points out that we deny the influence of culture when considering outstanding performers like Bill Gates and the Beatles.

The airline industry is a classic example cited in both books and across other industries as a benchmark for teamwork. The airline industry completely transformed their culture in a short period of time. The risk of unintentional death in an airplane declined from one person in 2 million in the 1970s to 1 in 8 million in during the 1990s as a result of programs for setting and enforcing teamwork standards established by the FAA. This feat was accomplished during a period when air travel (takeoffs, landings) had increased dramatically, which proves that swift and complex change can occur in a relatively short period of time.

Another example of the power of culture is found in Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers.” Gladwell describes the transformation of Korean Airlines flight crew culture away from a culture of deference and into a culture of candor. “Their problem was that they were trapped in roles dictated by the heavy weight of their country’s cultural legacy.” In short, David Greenburg, says, “We took them out of their culture and re-normed them.” The results? They’ve been a great success. They all changed their styles. They take initiative. They pull their share of the load. They don’t wait for someone to direct them. These are senior people in their fifties with a long history in one context, which have been re-trained and are now successful doing their job in Western cockpit. (Page 220)

Still, we the public, persist in thinking of pilots as solitary, elite leaders. On January 14, 2009, US Airways Flight 1549 was forced to crash-land in the icy Hudson River in New York, saving the lives of all 155 people on board. The National Transportation and Safety Board said the landing was the “most successful ditching in aviation history.” The press called it the Miracle on the Hudson.

Despite repeated insistence by pilot Captain Chelsey B. Sullenberger III that the entire crew, not him, were responsible, that’s not what the public wanted to hear. Instead, The New York Post headline read, “Quiet Air Hero is Captain America.” ABC News called him, “Hudson River Hero.” The German papers called him “Der Held von New York. The French “Le Nouveau Heros de l’Americue,” the Spanish language press “El Hero de Nueva York.” George W. Bush phoned him personally to thank him, and president-elect Barack Obama invited him and his family to attend his inauguration five days later. Photographers tore up the lawn of his Danville, California, home trying to get a picture of his wife and teenage children. He was greeted with a hometown parade and a $3 million book deal. Reporters at a press conference with the entire crew tried another angle with Sullenberger, pointing out his experience flying gliders as an Air Force Academy cadet. “That was so long ago, and those gliders are so different from a modern jet airliner. I think the transfer of experience was not large.” He just would not play along.

It was as if we simply could not process the full reality of what had been required to save the people on that plane, the same way we don’t see how outliers are a product of the cultures in which they grow up. This worldwide reaction sends a strong message about how deeply ingrained individualism is in Western cultures.